Mikkel has been the chief negotiatior for “eReolen” – the Danish public libraries’ national e-lending service – since 2017 as well as its lending model and financial model architect. eReolen has as far as we know the most loans per citizens per year of any public library e-lending service anywhere with 1.33. Denmark has a population of 5.8 mn., and 725.000 of them are active users of eReolen. The thoughts here are his own.

Introduction

E-lending is a wondrous but also dangerous thing. The benefits of e-books and digital audiobooks to the reader are well-known. Indeed the digitization of the audiobook has been even more consequential than the book and is in the process of changing the book market and literature consumption as we know it.

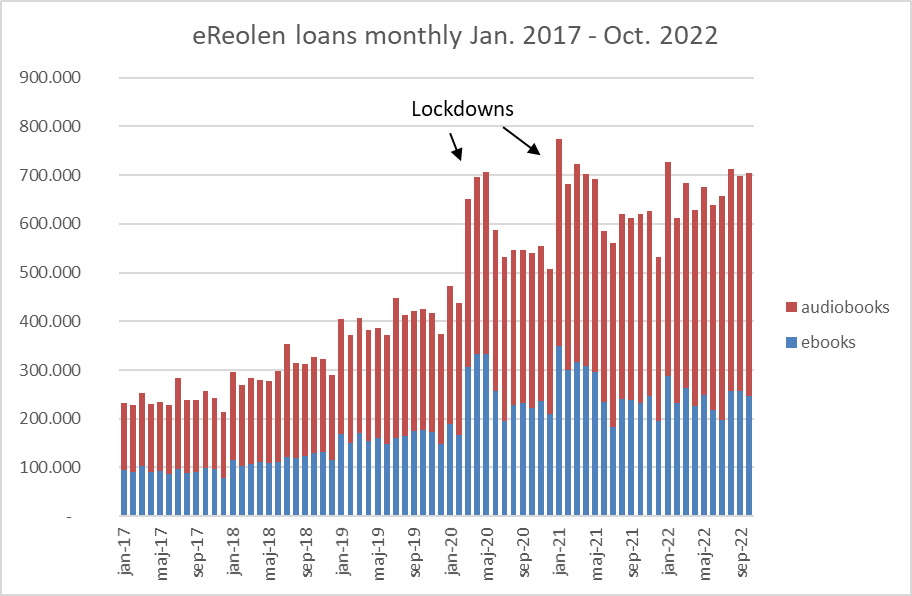

For libraries e-lending meant the ability to have a library offer available during the lockdowns ’20-’21 when many patrons needed it and the physical institution was closed. However, e-lending presents the public library with a range of existential threats, that include but are not necessarily limited to the ones I describe below. I’m not getting into price and copyright issues which otherwise dominate the e-lending debate. The reason is that we need to discuss not only the problems of building a successful e-lending service including solving procurement but also the consequences of possibly succeeding.

2021 became the first year in Danish history to see more digital library borrowers than physical ones. Physical loans were hampered by lockdowns in the beginning and end of the year of course but looking at the evolution of e-lending over the last decade it’s clear that the two pandemic years merely accelerated existing trends rather than constituting an actual change in the underlying state.

Even before the lockdowns those of us who are lucky enough to spend our life in the trenches on the battlefront of e-lending had begun to eye trend lines wearily and silently wonder where all this was headed. When library budgets stay flat while digital lending is soaring, digital demand can only be met by taking from the physical library. Looking strictly at loan numbers what is the endgame here? 40% physical and 60% digital? 20%-80%? 0%-100%? Probably not the latter but then where is the top exactly? “We shouldn’t worry too much about that. As long as people are reading it doesn’t matter if its physical or digital” is an argument I sometimes hear. I’ve heard it called the agnostic position and it always sends shivers down my spine for reasons that will be apparent shortly.

International collaboration and knowledge sharing has mostly focused on the challenges of acquiring digital titles; i.e. copyright and pricing issues. Little work has as yet focused on the challenges of what to do after acquiring them; i.e. the impact on services, programs, budgets, the library profession, competency development and indeed the very raison d’être of the public library in the long term.

Physical and digital lending is not the same

Physical lending and digital lending are not two sides of the same coin. One is enshrined in law, the other is not and relies on bilateral negotiations. One makes the library an owner, the other a short-term leaser. One has more than a century of public mandate and support, the other is an open question not yet asked. One is in local competition for your time, the other is in global competition for your attention. One draws you into the physical library with different benign effects – you’re available to aid your fellow patrons, you’re amenable to promotional efforts from the library and if nothing else you’re voting for the library with your feet – the other allows you to sit at home not necessarily being aware you’re using a library service. I could go on, but I’ll just note this: They are only complimentary with the greatest of care and the clearest of strategies. Failing that, digital lending will grow unchecked and feed parasitically off the physical library until a breaking point. However, taming digital lending with, say, draconian budget restraints carries with it dangers of its own. Death by parasite, incidentally, is called parasitoidism. We had to look it up.

Most libraries have become dependent on digital lending when it reports numbers back to funding bodies. They rightly fear library bypass if they don’t offer a competitive digital service, but the provision of digital content is a blood-red ocean filled with gigantic, cash-flush predators and a small, underdeveloped digital library service faces a perilous life when patrons choose how to allocate their precious time.

I’m here graciously only hinting at the fact that the value-adding services of the library – editorial work, discovery etc. – once subjected to the cruel, comprehensive visibility of the open internet faces competition of quite a different caliber than say the local event does when compared to other events in the area. This may sound like a contradiction. After all, how can the library be threatened by digital success and simultaneously by insufficient quality? I would argue that precisely this paradox is forcing the library into an unpleasant market position where the purely transactional access is interesting for the patrons – can’t beat free, right? – but the library’s heart blood, the value-adding services, are bypassed. I would further argue that that is where we find ourselves presently with our digital libraries. They are transactional services imbued with some value-added services – some have few, some have more – but in no way, shape or form are we as yet building something that might be called a digital public library.

Transactions without engagement

It looks like progress, but it’s really the opposite, because the relationship between patron and library is reduced to the barest minimum; the loan transaction. It is the ancient horror of transactions without engagement. All post-industrial marketing theory teaches us to develop not transactions but relations, loyalty and championship. This is impossible when we have much worse data on our digital users than our physical ones and when we allow aggregators such as Overdrive and Bolinda to often simply be the library and the library to be a subscription option to these giant actors. In Denmark, we build our own frontends, so we don’t send our patrons somewhere else for their e-books, but we struggle just the same just getting to know our digital users.

The end result is this: there is existential danger in not having a well-functioning digital lending service – perhaps only eclipsed by the dangers of having one.

In summary:

- All public libraries (to my knowledge) include digital loans in their total loans figures. We depend on digital loans to show stable or increasing activity. However, unchecked, digital loans will grow out of control and threaten the physical library which is the only place to find the resources necessary to support digital. E-lending lives parasitically off the physical library, and we have yet to determine the endgame for it.

- The agnostic view that all reading is good and that it doesn’t matter if our patrons ready physically or digitally is dangerous, because the two are not the same and carry with them very different notions of what the library is and should be.

- The most critical difference is that e-lending as designed now reduces patron’s interaction with the library to the basic transaction of the loan and may even take place on someone else’s platform. In the physical library, the patron gives something back. If nothing else their very presence. Online we know little about them and have yet to find way of bonding with them and develop relationships and loyalty.

- The online marketplace for digital media is a blood-red ocean with many giant players. Public libraries are as yet ill equipped to compete armed with library virtues and often end up being a one-trick-pony: we’re free! This is not where you want to be.

Part II: “Taming the parasite” up next.