-

Feudalism, capitalism and the challenge of digital transformation for public libraries

This post suggests a historical precedent for the current challenges of digital transformation and public libraries: the shift from feudal to merchant power in the middle part of the second millennia.

In his books Technics and Civilization Lewis Mumford writes about how technics (the total technological capacity of a society) and capitalism developed and influenced each other. Early in his book he talks about the nature of feudalism and how control of the land gave certain wealthy people domain over businesses like “glass-making, coal-mining and iron-works, right down to modern times.” However, “mechanical inventions lent themselves to exploitation but the merchant classes. The incentive to mechanization lay in the greater profits that could be extracted through the multiplied power and efficiency of the machine” (26)

Feudal land owners may provide a useful, if unlikely, historical analogue to public libraries. Both were defined by their specific location; their physical geography and relationship to people nearby. (Obviously the analogy has nothing to do with the nature of the relationship as feudal leaders subjugated their neighbors for profit while libraries seek to uplift their community.)

Does Mumford provides a warning for the present application of eBooks in public libraries?

“The handicraft industries in both Europe and other parts of the world were recklessly destroyed by machine products, even when the latter were inferior to the thing they replaced: for the prestige of improvement and success and power was with the machine, even when it improved nothing, even when technically speaking it was a failure.” (27)

There is a chance that libraries and communities will adopt eBooks as a technology even if the thing it is replacing is better due to perceptions of prestige. Mumford provides precedent to suggest that even if society decides to replace libraries with eBooks there is no guarantee that eBooks will provide a better service to the community than what came before.

-

Managing e-lending, part 2: Letting loose

The list

There’s little reason to believe the physical library can contain an e-lending service unless it’s very tightly controlled as described here. The demand for especially digital audiobooks is continuing unabated and control mechanisms tend to be crude and self-harming as described here. The alternative then is to embrace the digital literature in all its expanding glory and give it a home of its own; i.e. an actual digital public library.

Whether a digital library can ever be a library in the sense that we understand a public library or whether the two can co-exist peacefully perhaps even with some synergy, I’ll leave to deeper thinkers than myself. Evidence suggests there won’t be much interaction between the two. However, the objectives and ultimate yardstick of success are similar in many ways. See below.

First, I want to touch upon a list that my co-blogger wrote down a while ago. He’s graciously allowed me to use it even though it’s only a sketch. The list enumerates necessary steps to solving e-lending. At least the acquisition part of it.

The Swarthout list (a sketch):

- Clearly define a target audience and a collection

- Be able to access the needed titles viz. cost and T&Cs

- Get the service into the hands of the intended users

- Have appropriate control of the technology

- Resolve the issue of whether we need to own the books

- Maintain a stable relationship with publishers

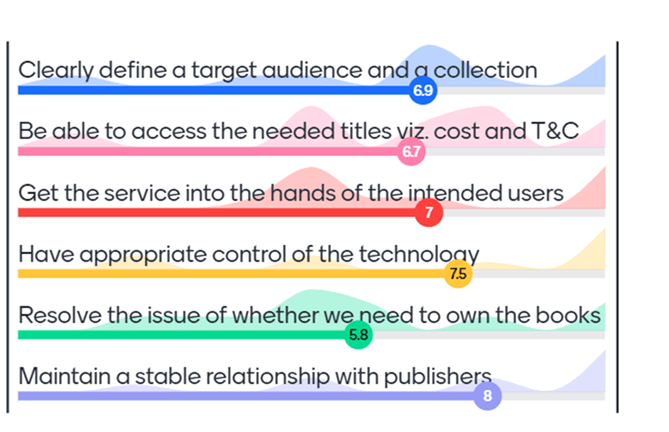

I ran it by the NAPLE expert group on e-lending and asked them to rate the items with each participant having 100 points to distribute among the items on the list. It was a close race!

Fig. 1: Voting on the list items

The acquisition part is causing major issues all over the world especially in the English-speaking world, but of course solving the acquisition issue is just half the battle. Just as Cato, the Roman senator, relentlessly pushed his main geopolitical idea by ending all his speeches with “Furthermore, I believe that Carthage must be destroyed,” I have ended all my communications on e-lending with “Furthermore, we need to talk about all the consequences of a possibly successful e-lending scheme.” Again; see this post for more on that.

What a digital public library might look like in broad terms and why it might not be that different from its physical sibling, I’ll introduce by presenting the Copenhagen value pyramid for libraries and a quick thought experiment.

The pyramid

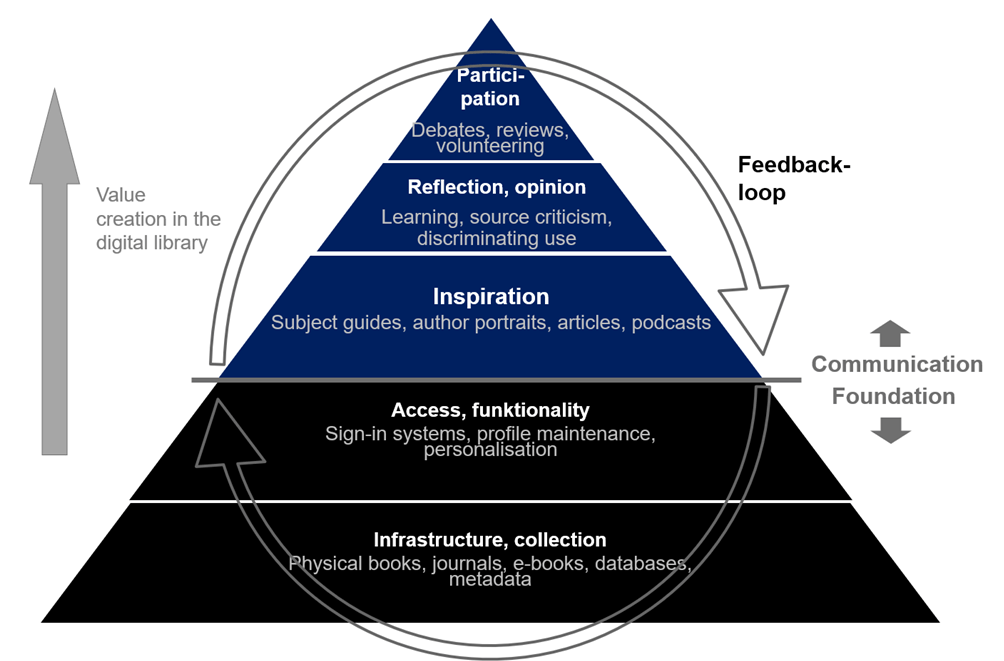

One of the best illustrations of what a digital library should do is by my boss in Copenhagen, Jakob Heide Petersen, who produced a hierarchy of value adding in the library in the form of a pyramid. Tellingly, it started off describing the physical library and was later modified to describe the digital library. If hardly solid proof it does indicate that despite all their differences the physical and the digital library are closely related. Note that the digital library here is envisioned as a gateway to the physical library as well.

Fig. 2: Adding value in the digital library

The pyramid is split in two parts consisting of two infrastructure steps and three communication steps respectively with feedback loops between the two parts. As I tend to accuse e-lending for reducing the library to transactions without the engagement, I’ll rename the top part the engagement part in the future.

The higher you go in the pyramid the more value the library has had for the individual patron. It doesn’t mean every interaction and relationship with patrons ends at the top or even should end at the top, but just that the most value is there.

The pyramid is read as follows. The library builds a technical infrastructure which is the basis for everything else. This makes possible the building of collections and services on top of the infrastructure.

With the infrastructure part in place, patrons can access the digital library and at the very least we hope to inspire them. Endless debates about what digital collections the library should have, what target groups if any and how to inspire patrons in what ways are certainly possible and should be had. In Denmark, children and young people are our primary target groups and the development policy for our digital collection – our e-lending platform – is focused on Danish literature, quality literature (as opposed to popular literature where these two differ), narrow literature and the back catalogue more so than the front.

Building on inspiration we hope to make patrons more discerning in their literary or cultural consumption. Indeed, the mission of Copenhagen Libraries is “Avid readers, discerning cultural consumers, engaged citizens.” The final step is to make patrons participate in cultural activities. This is where the library has had the biggest impact on the patron; added the most value.

What we learn about our infrastructure, collection and services by making them available to patrons will lead to necessary or strategic changes which in turn will change patrons’ use which will lead to further changes in an ever-ongoing feedback loop illustrated by the arrows.

Below I have re-arranged the Swarthout list in a way that makes the most sense to me and I have added a few words to item no. 2:

- Clearly define a target audience and a collection

- Be able to access the needed titles viz. cost and T&Cs while keeping total costs manageable

- Resolve the issue of whether we need to own the books

- Have appropriate control of the technology

- Maintain a stable relationship with publishers

- Get the service into the hands of the intended users

It’s clear that the list exhausts the acquisition part of the issues but also that it only barely breaks through the infrastructure – engagement barrier of the pyramid. We need a plan for the rest! Not only what but also how and by whom.

Joining the list and the pyramid and adding an item 7 to the list, it looks like this:

Fig. 3: The list and the pyramid: the case for item 7

Walking into Copenhagen Main Library

As a thought experiment let’s enter Copenhagen Main Library. The first thing to hit you when you’ve negotiated the revolving doors is the smell of coffee and freshly baked croissants from the café. Historically, this has ruined all attempts by me to stay off carbs. It’s also a little bit difficult to replicate online. Then you see the mainstays of all public libraries everywhere; books and visitors and upon closer inspection exhibitions and notifications of events and other offers such as book clubs, IT training classes etc. And staff.

Of course, a digital library will have books and lots of them. It can also easily offer online events and classes. We had great online events during COVID lockdowns. Also online book clubs, forums for discussion, all sorts of social interaction. A digital library can offer a plethora of literature promotion, discovery and other inspiration. Staff can run discussion boards, book clubs, do talks, be available for chat etc. The only real problem is the sense of physical space and human interaction in that space. You could argue that that is the game right there, but it’s not a problem isolated to the physical vs. the digital library, but rather everything physical vs. digital. I’m “working with the available nails” here as we say in Danish.

Better yet, in Denmark (5.8 mn. people) the public library is run by the municipalities of which there are 98. There are about 300 library locations in the country. Some of these are pretty small of course, but then much of the digital library could be national to ensure critical mass; e.g. enough people for the more esoteric literary interests and enough to merit an always manned chat hotline for instance. Also, Photoshop and Excel are similar in the north and south of Denmark. No reason to wait for your local library’s class to be filled. Literature promotion, inspirational activities, discovery etc. could be done by the best in the country and not the best in the municipality. This is essential when competing for people’s attention online as I’ve lamented before.

Best of all, though, there’s no reason this could not be the hub for all things literature drawing on the skills associated with librarianship as well as the reputation of the public library as one of the most trustworthy institutions in society (librarians place #4 in “most trustworthy profession” surveys in Denmark behind midwives, nurses and doctors respectively).

What we’re working in in Denmark is a bit different. Here, we’ve identified the local library as the primary hub, because the institution in people’s hearts and minds is the local library, and the local library is the one fighting for municipal funding. However, the local library should not spend its limited resources fighting a national or even international war for attention and traffic and so it will draw upon national services which will populate the web site and give access to national coordinated services such as eReolen through apps. And so most things digital will be nationally coordinated, but the local library is the sender.

PS: Two years ago while we were talking about the effects of lockdowns on digital literature use while walking through a beautiful wintery park in Copenhagen, the sales exec of the largest Danish digital publishing house said to me somehting to the effect of: “I really think the public library should build a national digital branch; a national digital library. THE place online for literature. You’re the only institution able to build such a site. Anything commercial will be limited and skewed. I also think you need to!”

—

Next up: The rise and rise of audiobooks

-

Managing e-lending, part 1: Of cubs and lions

Introduction

In my previous post I described some of the dangers of e-lending growth in the public library. I used the simile of a parasite. For variety’s sake I’ll change the image to that of the hunter and the lion in the Greek tragedy “Agamemnon” by Aeschylos from 458 BC. In a famous passage the choir is using a parable to describe the havoc created by (it is generally agreed) Helen of Troy. The parable is of a hunter finding a lion cub and bringing it home with him. At first everyone loves the little bundle of cuteness but it grows and eventually shows its true nature by going on a killing spree. The man’s sheep and his family end up massacred by this “priest of destruction.”There seems to be two ways of living with a lion. Either make it stay a cub or change the environment to accommodate a full-grown lion. The simile is getting a bit stretched here I admit. The principle at work should be clear enough though. Either control e-lending early in its development or let it grow while it changes the library whether you want it to or not. Digital content delivery free at the point of use WILL grow if not reigned in. As with lions; control them or they will devour you, your family and your sheep too.

Of these two strategies the latter is by far the more interesting, but also existentially much more challenging. It will be dealt with in part II. And then there’s the third way which can’t be recommended, but which I have seen in practice in more places than I had hoped; just don’t think too much about it. E-lending is making up for the steady loss of physical lending. What’s not to love?

The tools

Keeping e-lending down and manageable involves well-known tools such as loan limits, collection restraints and user restraints – i.e. who can become a user – and various artificial obstructions to use of the service. Of these, loan limits of various types are the most prolific. The tools come in the form of:A limit on loans

- In my experience this is almost universally used, but some municipalities in Denmark allow for limitless loans. Some regions and countries with very small collections also allow for near unlimited use.

- Some limit varieties come with the ability to return loans freeing up a slot. Some don’t and the book is yours for the fixed loan period of typically a month mimicking the standard physical loan period most places. See also below. This confuses users who will helpfully suggest the ability to turn in loans. They are ebooks after all so why not?

A limit on spending

- With metered access or one-copy-multiple-users being the norm most places the library knows its costs by buying licenses, but of course when the loans are gone there are just empty digital shelves until the next acquisition round.

- In other systems with one-copy-multiple-users or various pay-as-you-go solutions, libraries will typically set a limit on the monthly cost and/or the cost that any individual user can incur for the library. In this system, libraries may run out during the month and then open for business again on the first of next month. A bit similar to the empty digital shelves above but more predictable.

Collection restraints

- These are put in place by the library or publishers or both. This is where most of the international strife between libraries and publishers resides; what titles are offered to the libraries, at what cost and with what terms and conditions for use. Macmillan’s infamous “one license per library” policy is a case in point. When say New York Public Library can buy one license for a bestseller, use of the service will be limited to say the least.

- Libraries may restrict themselves to only buying some kinds of e-titles according to a collection development policy. In Denmark, we focus on the back catalogue, Danish literature, narrow titles and children’s literature. In Ireland, they treat the digital service more like the physical library and focus acquisition on new and popular titles. Logically, smaller, restricted collections have a correspondingly lower use rate than bigger, general ones.

- A tight collection development policy for smaller language countries or regions – the Estonias and Flanders and Norways of this world and hundreds of others – might kill two birds with one stone by really focusing on the national or regional literature. One bird being controlling the collection and thereby the number of loans, the other having a clear raison d’être and a cultural policy standpoint.

- Digital collections may shrink relatively speaking by being deprived access to many kinds of digital literature. Streaming services are making “originals,” that we are not offered and literature moves to new forms such as podcasts which is not our strength.

Quality of the service

- You wouldn’t think somebody would make a worse service than necessary to limit use, but that logic is in fact out there. A publisher once told me she was only comfortable with eReolen (the national e-lending service in Denmark), because it wasn’t as great as the commercial services; the technology, the features etc. She went on to explain: “I like the digital library to be the same as the physical one. Yes, you can get books for free, but you often have to stand in line and the books are a bit yucky and pee-y(!?)”

- To my knowledge, no library in the world has an e-lending service that matches commercial services in terms of functionality and yumminess of design, but in Denmark we have deliberately flown under the radar with frontends that emphasized the literature part and not the lending part. We’re making a virtue out of necessity, because we cannot match the development budgets of commercial services even if we wanted to and we want to be different anyway.

Obstructions

- This category is underdeveloped and there’s certainly room for creativity. A fixed loan period is an obstruction that few users really understand but serves as a crucial cost management feature in pay-as-you-go systems.

- Some have speculated in a basic service available for everyone, but enhanced services if you join a library club, sign up for a newsletter or turn up at the physical library. The latter is rather ingenious and has many things going for it. However, it’s very obvious what you’re doing and it is quite the insult to people living far from the library who were supposed to benefit from e-lending.

None of these are really … sexy. At the satellite conference on e-lending at IFLA 2022 in Dublin, Stuart Hamilton of LGMA Ireland and myself ran a vox pop at the end including the question: “What is your favourite way of stopping digital lending?” The participants’ fidgeting and protests trying to answer was obvious. The whole business is just against every fiber in every library person’s body.

Friction does work

Denmark has the highest e-lending figure per capita of any national public library service in the world, I believe (8 mn. loans versus 5.8 mn. Danes in 2022). Our growth owes itself to many factors but one of the most important ones – if not the most important one – is that we have made friends with publishers. We have a close collaboration with them, because we acknowledge each other’s reality and we have found a lot of common ground that way. One concession we have made on our part is one we happily made. We don’t try to compete with commercial services on new bestsellers. We’ve tried to turn it into a strength that we focus on all the rest; especially Danish literature, narrow titles and children’s literature. Our top-10 every year for both ebooks and audiobooks have 8-9 children’s titles on it and half of those will be older ones. We have embraced friction.We have also participated in large public-private partnerships on retro-digitisation of the Danish literary heritage. We helped select titles based on our specialized knowledge of library users, publishers digitised the books and we promoted these new old titles on eReolen. It turned out marvelously with retro-titles having the same number of loans as real new titles in the year of their entry. This did wonders for our kind of literature and solidified our brand in the eyes of all stakeholders.

If eReolen continues to grow at the rate of the last five years, the physical libraries cannot cope with their stagnant budgets. We will have to make further restraints on use or restrict the collection even further. There’s potential in cutting e.g. popular but lightweight literature such as translated romance or crime, but I also expect to see this kind of literature moving steadily to e-only making it more controversial to cut them from eReolen, but if we have to choose, I’d rather slim the collection that way than restrict all use.

A philosophical distinction

The most important factor to keeping the lion a cute cub versus letting it grow to more scary proportions is perhaps a philosophical one. E-lending has revealed quite a difference in how heads of libraries everywhere view the mission of the library and the role of its services. The differences in philosophy can be categorized in many ways and levels of granularity, but for our purpose here, the difference between what has been called (by my co-blogger) the agnostic view – i.e. it doesn’t matter how people read as long as they read – and the view that the library is first and foremost a physical institutions is important. With the first view e-lending may very well grow and grow, because it’s serving the purpose of reading (see my future post on the rise and rise of audiobooks though). E-lending is indistinguishable from the library’s core mission. With the physical view you will eye digital growth with suspicion and probably move to slow it down before it gets really out of hand though you may lack elegant tools to do so. E-lending in this view is a service among many and kept at that level.A Danish head of a large public library used a phrase the other day I found hilarious. He talked about “the unbearable yoke of physical lending.” It’s fairly easy to see which general view he holds. Another library exec just stared blankly at him and so I put her in my book under the other view. It’s interesting to see how the incessant growth of e-lending reveals basic and up until now unvoiced assumptions of the nature of the public library.

Part II of this post will deal with the arguably more exciting vision of changing the library to accommodate the digital transformation in all its fangy and clawy glory.

-

The parasitoidism threat of e-lending

Mikkel has been the chief negotiatior for “eReolen” – the Danish public libraries’ national e-lending service – since 2017 as well as its lending model and financial model architect. eReolen has as far as we know the most loans per citizens per year of any public library e-lending service anywhere with 1.33. Denmark has a population of 5.8 mn., and 725.000 of them are active users of eReolen. The thoughts here are his own.

Introduction

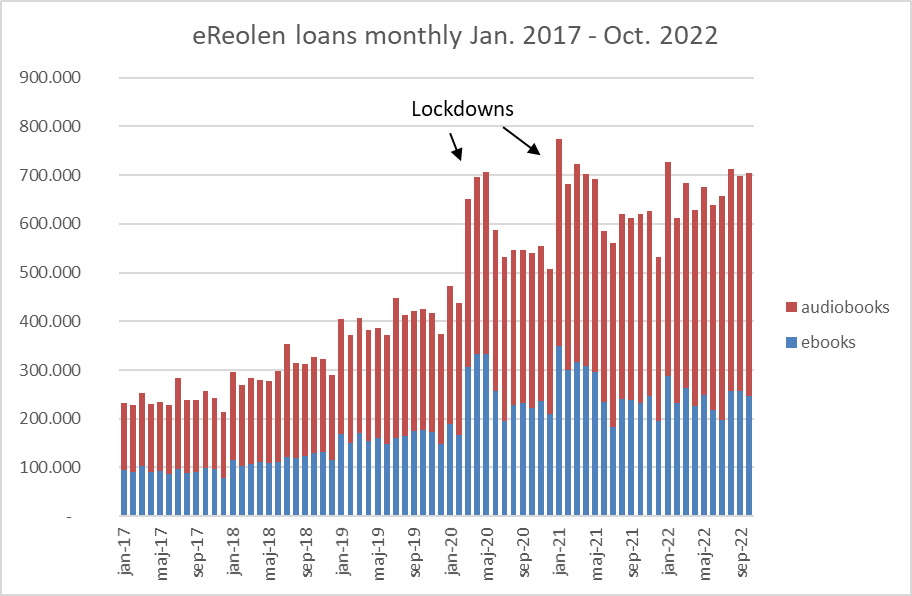

E-lending is a wondrous but also dangerous thing. The benefits of e-books and digital audiobooks to the reader are well-known. Indeed the digitization of the audiobook has been even more consequential than the book and is in the process of changing the book market and literature consumption as we know it.

For libraries e-lending meant the ability to have a library offer available during the lockdowns ’20-’21 when many patrons needed it and the physical institution was closed. However, e-lending presents the public library with a range of existential threats, that include but are not necessarily limited to the ones I describe below. I’m not getting into price and copyright issues which otherwise dominate the e-lending debate. The reason is that we need to discuss not only the problems of building a successful e-lending service including solving procurement but also the consequences of possibly succeeding.

2021 became the first year in Danish history to see more digital library borrowers than physical ones. Physical loans were hampered by lockdowns in the beginning and end of the year of course but looking at the evolution of e-lending over the last decade it’s clear that the two pandemic years merely accelerated existing trends rather than constituting an actual change in the underlying state.

Even before the lockdowns those of us who are lucky enough to spend our life in the trenches on the battlefront of e-lending had begun to eye trend lines wearily and silently wonder where all this was headed. When library budgets stay flat while digital lending is soaring, digital demand can only be met by taking from the physical library. Looking strictly at loan numbers what is the endgame here? 40% physical and 60% digital? 20%-80%? 0%-100%? Probably not the latter but then where is the top exactly? “We shouldn’t worry too much about that. As long as people are reading it doesn’t matter if its physical or digital” is an argument I sometimes hear. I’ve heard it called the agnostic position and it always sends shivers down my spine for reasons that will be apparent shortly.

International collaboration and knowledge sharing has mostly focused on the challenges of acquiring digital titles; i.e. copyright and pricing issues. Little work has as yet focused on the challenges of what to do after acquiring them; i.e. the impact on services, programs, budgets, the library profession, competency development and indeed the very raison d’être of the public library in the long term.

Physical and digital lending is not the same

Physical lending and digital lending are not two sides of the same coin. One is enshrined in law, the other is not and relies on bilateral negotiations. One makes the library an owner, the other a short-term leaser. One has more than a century of public mandate and support, the other is an open question not yet asked. One is in local competition for your time, the other is in global competition for your attention. One draws you into the physical library with different benign effects – you’re available to aid your fellow patrons, you’re amenable to promotional efforts from the library and if nothing else you’re voting for the library with your feet – the other allows you to sit at home not necessarily being aware you’re using a library service. I could go on, but I’ll just note this: They are only complimentary with the greatest of care and the clearest of strategies. Failing that, digital lending will grow unchecked and feed parasitically off the physical library until a breaking point. However, taming digital lending with, say, draconian budget restraints carries with it dangers of its own. Death by parasite, incidentally, is called parasitoidism. We had to look it up.

Most libraries have become dependent on digital lending when it reports numbers back to funding bodies. They rightly fear library bypass if they don’t offer a competitive digital service, but the provision of digital content is a blood-red ocean filled with gigantic, cash-flush predators and a small, underdeveloped digital library service faces a perilous life when patrons choose how to allocate their precious time.

I’m here graciously only hinting at the fact that the value-adding services of the library – editorial work, discovery etc. – once subjected to the cruel, comprehensive visibility of the open internet faces competition of quite a different caliber than say the local event does when compared to other events in the area. This may sound like a contradiction. After all, how can the library be threatened by digital success and simultaneously by insufficient quality? I would argue that precisely this paradox is forcing the library into an unpleasant market position where the purely transactional access is interesting for the patrons – can’t beat free, right? – but the library’s heart blood, the value-adding services, are bypassed. I would further argue that that is where we find ourselves presently with our digital libraries. They are transactional services imbued with some value-added services – some have few, some have more – but in no way, shape or form are we as yet building something that might be called a digital public library.

Transactions without engagement

It looks like progress, but it’s really the opposite, because the relationship between patron and library is reduced to the barest minimum; the loan transaction. It is the ancient horror of transactions without engagement. All post-industrial marketing theory teaches us to develop not transactions but relations, loyalty and championship. This is impossible when we have much worse data on our digital users than our physical ones and when we allow aggregators such as Overdrive and Bolinda to often simply be the library and the library to be a subscription option to these giant actors. In Denmark, we build our own frontends, so we don’t send our patrons somewhere else for their e-books, but we struggle just the same just getting to know our digital users.

The end result is this: there is existential danger in not having a well-functioning digital lending service – perhaps only eclipsed by the dangers of having one.

In summary:

- All public libraries (to my knowledge) include digital loans in their total loans figures. We depend on digital loans to show stable or increasing activity. However, unchecked, digital loans will grow out of control and threaten the physical library which is the only place to find the resources necessary to support digital. E-lending lives parasitically off the physical library, and we have yet to determine the endgame for it.

- The agnostic view that all reading is good and that it doesn’t matter if our patrons ready physically or digitally is dangerous, because the two are not the same and carry with them very different notions of what the library is and should be.

- The most critical difference is that e-lending as designed now reduces patron’s interaction with the library to the basic transaction of the loan and may even take place on someone else’s platform. In the physical library, the patron gives something back. If nothing else their very presence. Online we know little about them and have yet to find way of bonding with them and develop relationships and loyalty.

- The online marketplace for digital media is a blood-red ocean with many giant players. Public libraries are as yet ill equipped to compete armed with library virtues and often end up being a one-trick-pony: we’re free! This is not where you want to be.

Part II: “Taming the parasite” up next.

-

Technology, public libraries and digital transformation

For the past one hundred and fifty years the idea of the public library has evolved alongside rapid technological change. Many of these changes (broadcast media, for example) were viewed, at the time, as potential threats to the sector. Despite these fears, libraries adapted and continued to thrive. Predicting doom for libraries has been a failing business for nearly a century. Nevertheless, the collection of technologies described as “the internet” pose a new and unique set of challenges to the persistence of public libraries.

Technologies have been critical to the creation and development of public libraries.

The written word, the printing press, and mass printing were all crucial building blocks for the creation of public circulating libraries in America starting in the nineteenth century. Widespread literacy and durable, affordable books were the necessary preconditions for the development of public libraries as we know them.

New technologies in the past hundred years have also enabled (and eliminated) new library offerings and services. Moving pictures were not a library offering until the creation of film strips and later VHS cassettes and DVDs. Music was not lent broadly by libraries until the invention of the vinyl record and later the cassette and CD. The changes in technology that brought about streaming audio have greatly reduced the role of recorded music in public library collections. Today’s digital transformation represents only the latest in a series of technological changes that libraries have experienced and weathered over the last two centuries.

The collection of technologies that we commonly call “the internet,” are the most transformational since the founding of libraries.

Digital technologies have a number of particularly disruptive effects on libraries. They eliminate the need for some services, invite opportunities for libraries to serve new patrons, and reveal unmet demand for existing services. Perhaps most significantly, internet enabled technologies allow libraries, for the first time in their history to imagine the provision of their services, or at least a facsimile of them, without their buildings, physical collections or even certain types of staff.

All prior technologies merely augmented the basic concept of a public library (building + books + patrons + staff = platform). However, the internet presents the possibility of radically transforming the concept of a public library. It also presents the possibility of changing libraries in such a way that undermines the broad public support that has been crucial to their continued existence in America.

Libraries are clearly not alone in being buffeted by the changes created by the internet. If anything, libraries have remained immune for longer than most other sectors. So long, perhaps, that some of its staff may think that public libraries can continue to remain immune to the pressures created by digital technology.

Public Libraries have always existed to serve multiple purposes.

Throughout their history public library leaders have taken very different views about the purpose – and beneficial impact on society – of public libraries. This ambiguity has allowed for “interpretive flexibility” among library staff, the general public and the donor class that financially support public libraries, albeit for different reasons. Everyone can see libraries differently.

Even among the library sector’s leaders and most ardent supporters there have been differing opinions on what the purpose of the library.

- Melvil Dewey created the system that organized non-fiction library books but placed much less emphasis on fiction.

- Andrew Carnegie had a very clear vision of public libraries as enabling individual advancement, to the benefit of business and commerce.

- At the end of World War I the library director of Newark, NJ declared that the public libraries were failures because they had not stopped global conflict.

- After World War II the Public Library Inquiry reported that librarians believed their role was to provide broad public education.

- In the 1970s the director of the Queens Public Library believed that libraries existed largely to support the formal education system.

- Some librarians have been against popular fiction while others have been their champion.

- Some have quietly supported community censorship, while others have railed against it.

Nevertheless, in spite of these divergent opinions on the “why?” of the library, the “what” has remained constant: a stable building, a circulating collection, a trained staff and uninhibited patrons.

Does there need to be a single answer to the question, ‘why do libraries exist?’

For nearly their entire history American public libraries have weathered the critique that they should think more strategically or face elimination. Libraries have persisted in communities despite largely dismissing these warnings. In doing so they seem to have proven all of their critics more or less wrong. Therefore, anyone forecasting the demise of libraries at the hands of “the internet” should be cautious. And yet the power of digital technology to transform industries demands its own respect.

Digital technologies can unbundle the traditional public library so that some of its core services (book lending, public programs, education, listening to audiobooks, watching films) appear to be able to exist without some – or all – of its patrons ever entering the branch or interacting with neighbors or library staff. In the process of disaggregating public libraries are at risk of turning down or outsourcing services that were key to their value or public support. Separating the library into a set of distinct services, with some online and some in person, could pierce the halo around the institution that has contributed to its broad support from across communities and make that interpretive flexibility more difficult. Thus while digital offerings can be exciting opportunities to extend the reach of the institution they can also threaten the social contract with the public that allows libraries to receive stable funding from their local government.

The question of dealing with digital transformation is ‘how can libraries continue to satisfy the public?’

Digital transformation has brought an end to countless companies and ideologies. It has brought obsolescence to untold numbers of technologies, businesses, services and products, many previously considered to be unassailable. Libraries are not threatened because they have diminished value, they are threatened because digital technology rearranges the world around them.

The task of libraries in the face of digital transformation is twofold: persist, for as long as possible, while determining whether, by the strategic application of new technology, they could use digital technology to deliver greater value and benefit to society.

-

eBooks present public libraries with a new supply chain challenge

This is adapted from a presentation that I have made occasionally over the past several years. It attempts to explore the challenge that public libraries face with publishers around eBooks, touching briefly on issues of copyright but framing the question as one of supply chain strategy. I have inserted my slides and added my talking points/notes below.

- Looking back over the past ten years, libraries have experienced a succession of changes in terms and pricing models as publishers try to figure out eBooks.

- This led to libraries occasionally losing access to some books and seeing price hikes on others.

- When Overdrive negotiated with Amazon to load library eBooks on the Kindle, Penguin pulled their books from Overdrive. There is no historical precedent for libraries losing access to books in the past hundred years.

- Most recently, in 2019 Macmillan publishing proposed embargoing their new eBook releases for two months to stop libraries from impacting sales.

- Price hikes are a problem.

- Losing access to books is a problem.

- Instability is a problem.

- Public libraries are unable to develop technology, train staff or set patron expectations for this growing service of the library if we can’t have greater comity with publishers.

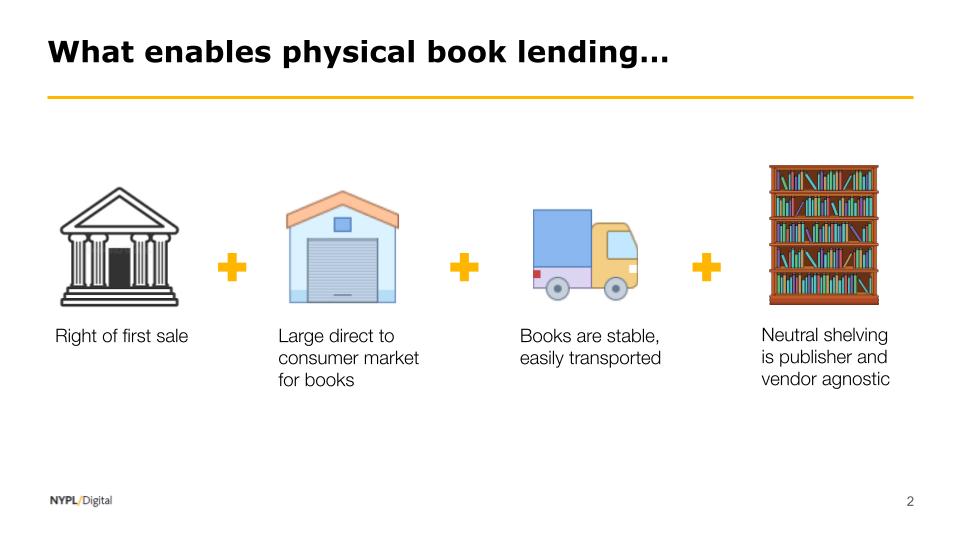

- We take for granted that public libraries are able to buy print books. This ability is a function of laws, the technology of the printed book and the consumer market for print books.

- First, the right of first sale enables anyone who purchases a print book to redistribute that object. It applies to books but also CDs, cassettes, used cars. Its fundamental to American public libraries. (A lot of attention in the public library sector is focused on the question of digital right of first sale. Right of first sale is clearly a very important question but it’s only one part of the equation allowing for a stable public library print market.)

- Second, public libraries can purchase the same physical books as private consumers. Because libraries only account for only about 10% of trade book sales, publishers price their titles to the larger market, not the ability of libraries to pay. Even if a library would be willing to pay more than $30 for the latest hardcover, a publisher has a very difficult time extracting that from a library. (This is notably different than the scholarly market where libraries are often the primary purchasers and publishers engage in this type of monopolistic pricing. This is one of the reasons that it is difficult to talk about academic and public library eBooks at the same time. Even the choice to talk this broadly about “public library eBooks” is an over-generalization.)

- Third and sometimes overlooked is the marvelous technology of the pint book which is transportable, durable, and communicates a tremendous amount of information. Without the physical book we couldn’t have lending libraries.

- Finally, libraries possess neutral shelving that can hold books purchased from any publisher. This seems like an outlier but you’ll see how different things look digitally.

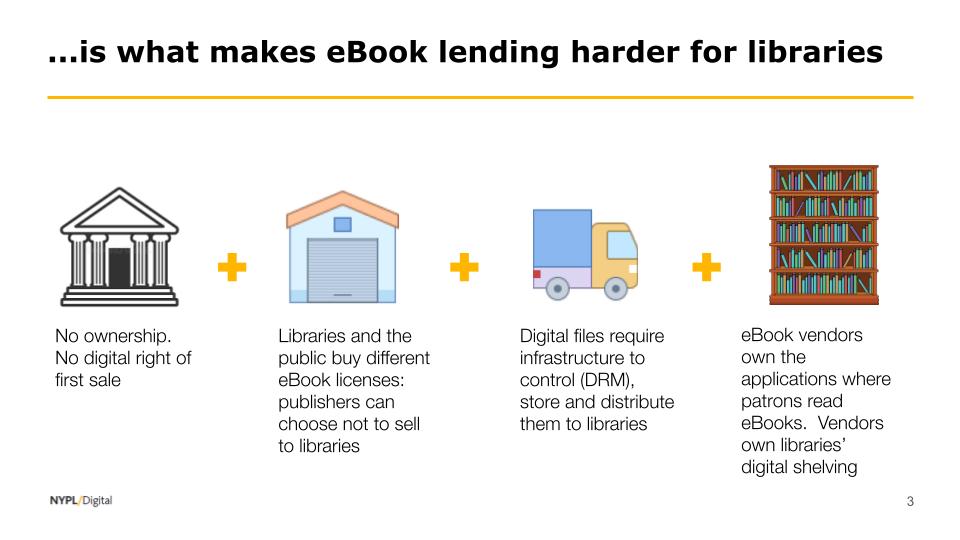

- None of these conditions are in evidence when it comes to eBooks.

- There is no confirmed first sale doctrine for software. Most publishers do not sell eBooks to libraries, they license them the same way Microsoft licenses Word and Excel. These licenses prescribe the terms under which we can lend eBooks. This will make sense if anyone has ever tried to give away their copy of Word.

- Second, because libraries are seeking to buy a bundle of licenses publishers are able to segment libraries and set different pricing.

- Third, while the digital file is wonderful in some ways, it has its own challenges to manage and control. That creates costs, requires digital rights management technology, and introduces middlemen into the process.

- These middle men, like Overdrive in the US, for most libraries provide not only the file hosting but also display of eBooks through their proprietary eReading apps like Libby. That means libraries no longer have neutral shelving. They cannot licence an eBook from one vendor and have it seamlessly show up next to our other eBooks.

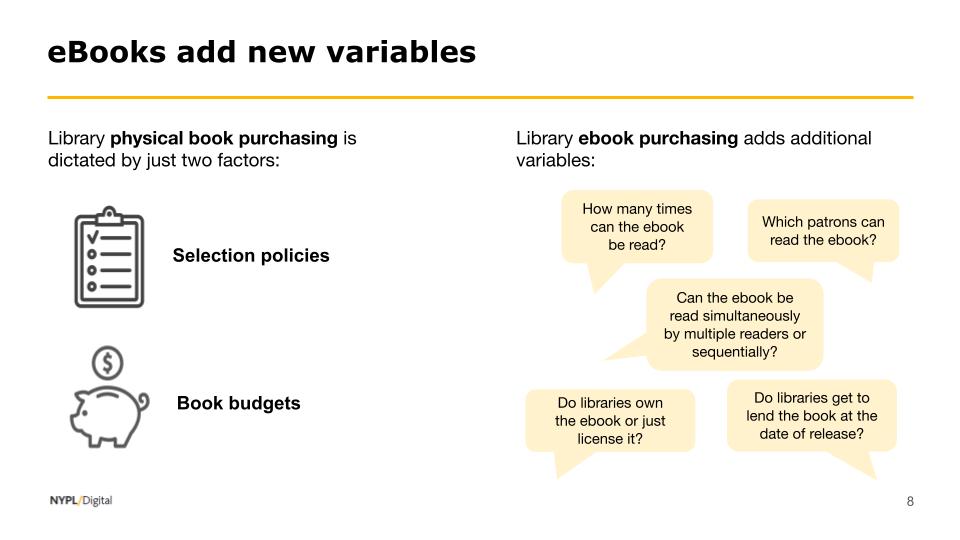

- I want to suggest that eBooks fundamentally changed the nature of the publisher/library relationship from one that was fairly hands off, to one that requires more active engagement.

- There is very little variation in print books. There is almost nothing for libraries and publishers to enter negotiations over.

- As a result libraries and publishers have very specific types of conversations led by library book selectors/buyers and publishing house marketers.

- When you are writing the permissions on a digital file there are an enormous number of variables that you can adjust. Some are listed above.

- Here is my understanding of how the terms for American public library eBook licensing evolved over time. About ten years ago, the major publishers started out licensing eBooks to libraries on a one copy, one user basis for a perpetual license at 5-10 times the list price. For example, a library could buy one electronic copy of the Secret Garden and have it forever to be used by one reader at a time. This looked like a good idea at the time and seemed to replicate the physical book market.

- However, publishers realized that for some titles they were losing the recurring revenue that came from a library purchasing new copies as old print copies wore out.

- Some publishers offered libraries the option to pay per use but this creates budget management challenges for libraries, like putting down a credit card without knowing how many people are going to be coming through the turnstiles.

- And where libraries and publishers have largely settled is one copy, one user model where libraries buy a package of lends. 26 lends or one year of use, whichever expires first.

- From this anecdote you can see that libraries are in a de facto negotiation with publishers however these discussions are almost entirely mediated by vendors or had through trial and error over years.

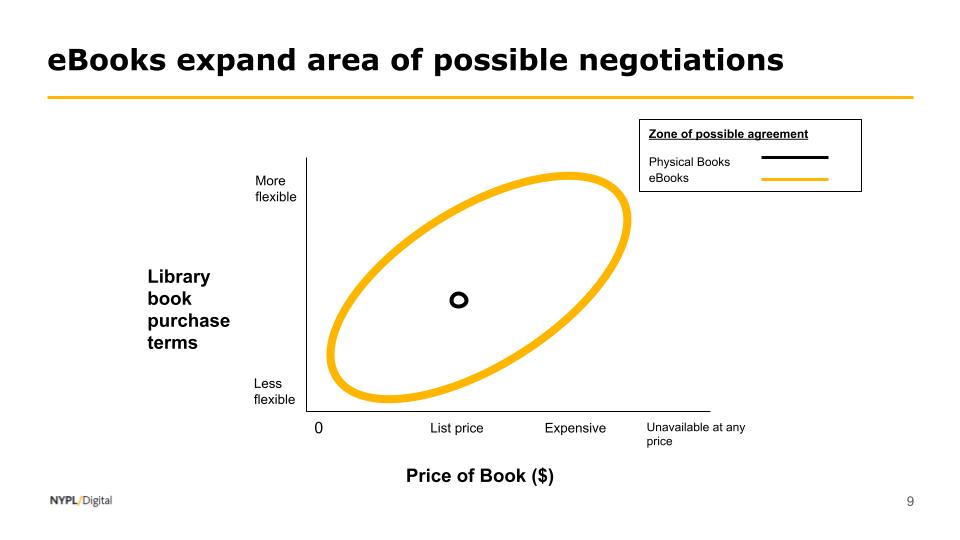

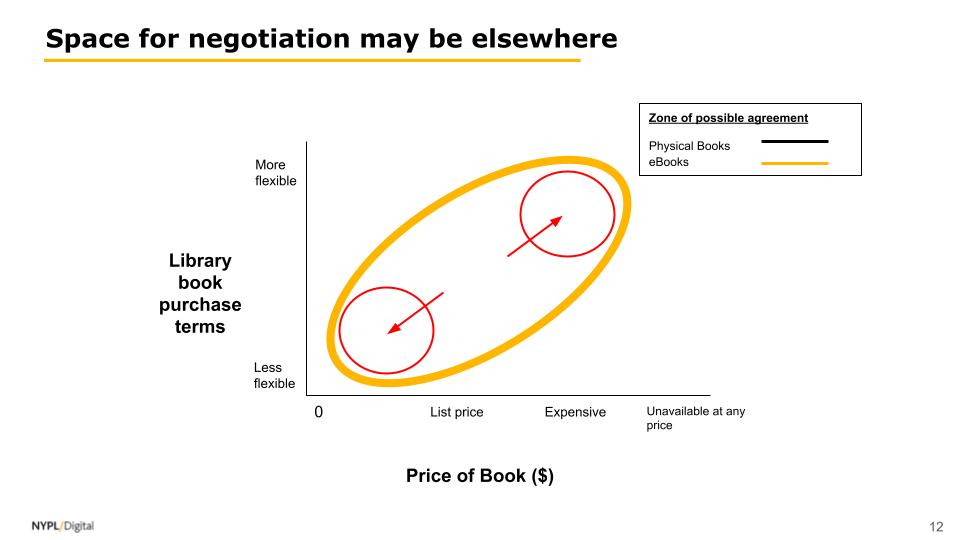

- This is an effort to visualize the change in parameters of negotiation for publishers and libraries.

- On the x axis is the price of the book. To the left it’s cheaper, to the right it’s more expensive.

- On the y axis are the terms. For the purposes of this image I’ve stuck to two dimensions so all the different variables we could negotiate on, other than price, are just lumped together. To the bottom is less flexible, to the top is more flexible.

- The black circle in the middle is the “zone of possible agreement” for print books. Public libraries can buy (or not buy) a print copy at roughly the same price as the average consumer. Even if libraries were inclined to sit down with publishers regularly there is not much to to negotiate. Publishers have a difficult time forcing libraries to pay over list price and libraries can’t offer publishers much to get them to lower their list price.

- By contrast, the yellow oval is the zone of possible agreement for eBooks. If libraries want multiple users at the same time, the price goes up. If they want it perpetually the price goes up. If the book is unpopular, the price could go down. If libraries can demonstrate our readers are not book buyers, the price could go down.

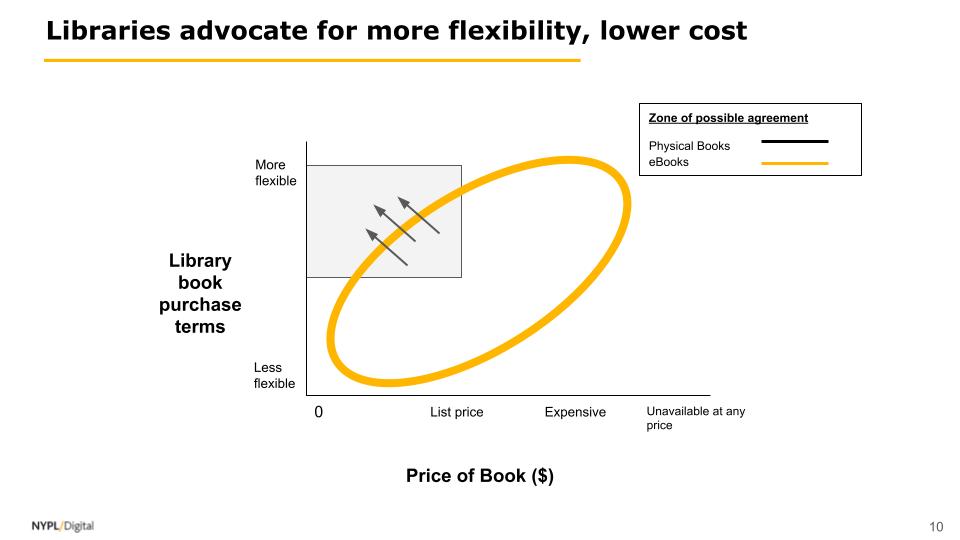

- For the past ten years public libraries have been advocating for cheaper pricing and more flexible terms. They want to push towards the top left quadrant.

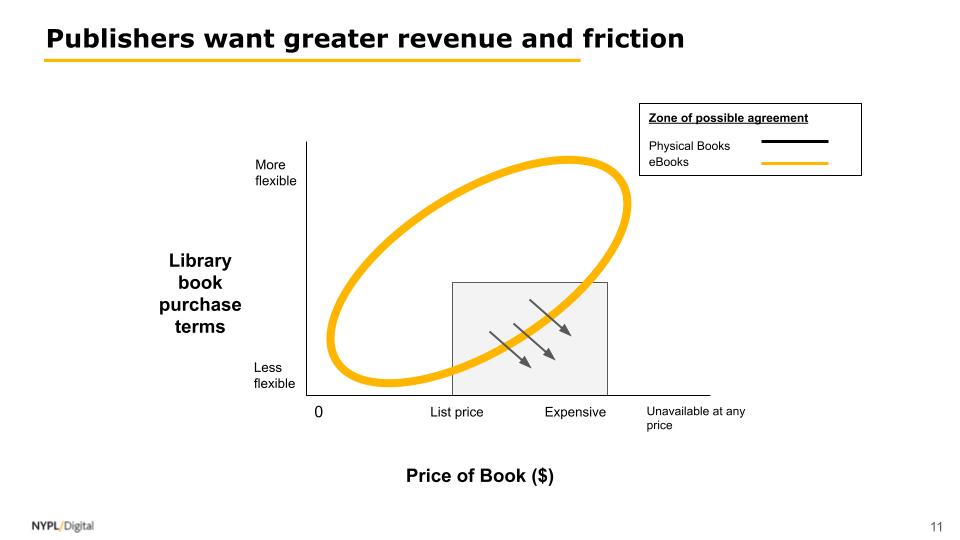

- Over the same time period publishers have been pushing for more expensive, less flexible terms.

- You can imagine how this has been going.

- In theory, there may be opportunity for libraries and publishers to explore areas for shared value.

- While this is mostly theoretical in the American market I can find evidence for it in Denmark with the work Mikkel has led. (More on this later).

- There is one other significant factor that needs to be addressed in the eBook supply chain and that is the role of the vendors who host our eBook licenses and also provide eBook apps used by every other public library in America. These middlemen have an enormous amount of power.

- Our print book vendors sell us books. Sometimes they do a little more to help us organize our data, but that’s about it.

- But because libraries aren’t technology companies, when our vendors started licensing eBooks to us they also needed to provide an app to read in.

- This app is the de facto digital library. It assumes almost all of the responsibilities of a normal branch library from organizing the titles, picking the target user, creating the user experience.

- Because libraries have very loose connections with patrons we have a difficult time telling patrons to switch apps. While a high school can tell students at the start of every year which apps to use, libraries tend to worry about losing readers when switching patrons from app to app.

- We’ve seen Overdrive make a series of strategic choices that change the willingness of publishers to do business with libraries. I mentioned one earlier. When they partnered with Amazon in order to help libraries serve their patrons, we lost Penguin book access. This dynamic has, to my eyes, no historical precedent for libraries.

Even if we can’t see it right now, what would success look like? This slide lays out a stab at an answer.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

It is very easy to see how digital technology has changed the reading experience of our patrons. It’s harder to observe how it has changed our business operations. We are at the beginning of thinking this through. And we are somewhat alone among our public library peers in doing this type of analysis. Which is why we’re excited to share it with you for thoughts and feedback and criticism.

-

This is the beginning

This is the beginning of a writing project about eBooks and public libraries.

Exactly no one will read this when it is posted. No one is waiting for our thoughts. But in case someone reads something that we write in a week, a month or a year, we will leave this note behind to explain who we are, what this is, and why we did it.

We met during the pandemic, virtually, as most people did during that time. We were introduced by our mutual colleague Ilona Kish. Probably we were the only two people who forced her to listen to long winding stories about eBook lending. Maybe she recognized two kindred spirits. Perhaps she was trying to save herself several hours a month. Regardless, we owe her a debt.

We are from different libraries, countries and continents, but we are united by the belief that the act of lending books electronically is consequential to the present and future of public libraries in Western Europe and the United States. And we share views that are slightly unorthodox for the public library sector.

Over the past several years we have given talks and written papers about eBooks and public libraries. However, more of our thoughts are locked up in our heads, squirreled away in unpublished documents or floating in ongoing conversations between the two of us. This increasingly feels unsatisfactory for three reasons:

- Each document we write or talk we give only tells part of the story. We believe that putting together our thoughts may add up to something larger and more coherent.

- We have been wrestling with these problems separately but suspect that doing so together may sharpen our thinking.

- Libraries are struggling with the problem of eBooks in real time. Our patrons are changing, the world is changing, and our institutions are changing, constantly. We do not have all of the answers, but we believe that the act of writing and thinking out loud, in public, may improve the clarity of our thoughts.

So then, what is this? This is an effort to share things we have already written, things we are writing together, discussions we have had or are having, the brilliant thoughts of others, in one place to ask the question: what is the future of eBooks and public libraries?

Beyond that, we’re still figuring it out. This is the beginning after all. An introduction to let readers know where we started. And perhaps, to let us know how far we have traveled when we get to the end.

-Luke and Mikkel

P.S. A brief note about the title of this blog. We called it this for three reasons:

- Naming is hard.

- It is technically true. Mikkel is in Copenhagen and Luke is in New York.

- We thought it was funny.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.