This is adapted from a presentation that I have made occasionally over the past several years. It attempts to explore the challenge that public libraries face with publishers around eBooks, touching briefly on issues of copyright but framing the question as one of supply chain strategy. I have inserted my slides and added my talking points/notes below.

- Looking back over the past ten years, libraries have experienced a succession of changes in terms and pricing models as publishers try to figure out eBooks.

- This led to libraries occasionally losing access to some books and seeing price hikes on others.

- When Overdrive negotiated with Amazon to load library eBooks on the Kindle, Penguin pulled their books from Overdrive. There is no historical precedent for libraries losing access to books in the past hundred years.

- Most recently, in 2019 Macmillan publishing proposed embargoing their new eBook releases for two months to stop libraries from impacting sales.

- Price hikes are a problem.

- Losing access to books is a problem.

- Instability is a problem.

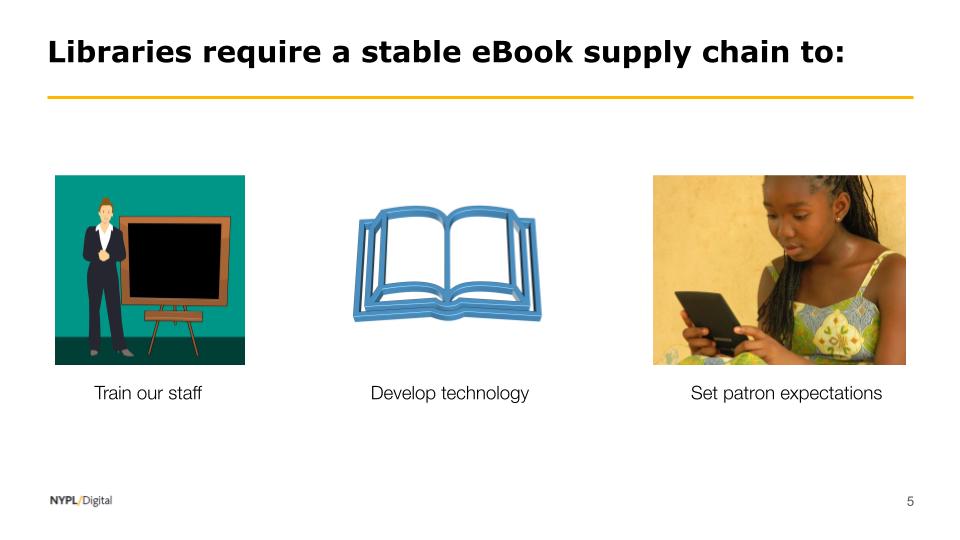

- Public libraries are unable to develop technology, train staff or set patron expectations for this growing service of the library if we can’t have greater comity with publishers.

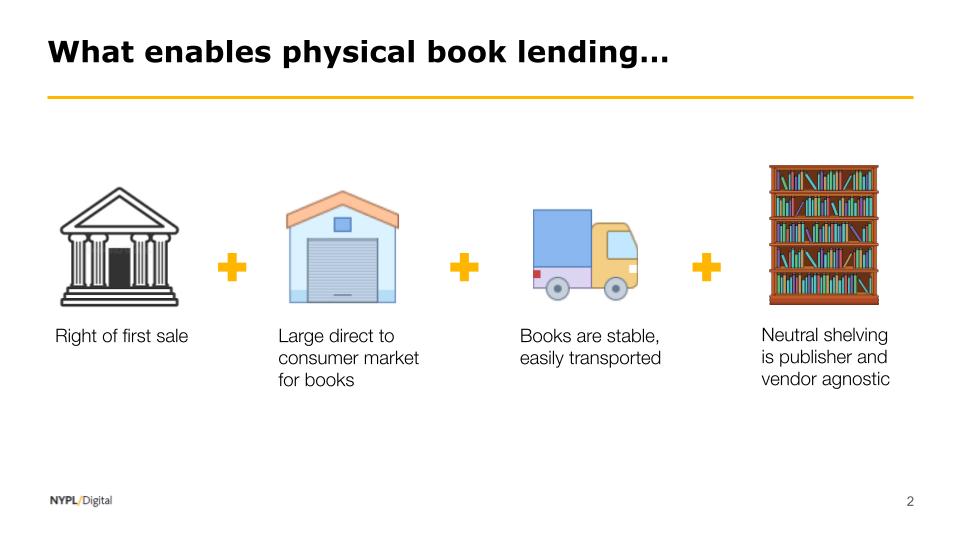

- We take for granted that public libraries are able to buy print books. This ability is a function of laws, the technology of the printed book and the consumer market for print books.

- First, the right of first sale enables anyone who purchases a print book to redistribute that object. It applies to books but also CDs, cassettes, used cars. Its fundamental to American public libraries. (A lot of attention in the public library sector is focused on the question of digital right of first sale. Right of first sale is clearly a very important question but it’s only one part of the equation allowing for a stable public library print market.)

- Second, public libraries can purchase the same physical books as private consumers. Because libraries only account for only about 10% of trade book sales, publishers price their titles to the larger market, not the ability of libraries to pay. Even if a library would be willing to pay more than $30 for the latest hardcover, a publisher has a very difficult time extracting that from a library. (This is notably different than the scholarly market where libraries are often the primary purchasers and publishers engage in this type of monopolistic pricing. This is one of the reasons that it is difficult to talk about academic and public library eBooks at the same time. Even the choice to talk this broadly about “public library eBooks” is an over-generalization.)

- Third and sometimes overlooked is the marvelous technology of the pint book which is transportable, durable, and communicates a tremendous amount of information. Without the physical book we couldn’t have lending libraries.

- Finally, libraries possess neutral shelving that can hold books purchased from any publisher. This seems like an outlier but you’ll see how different things look digitally.

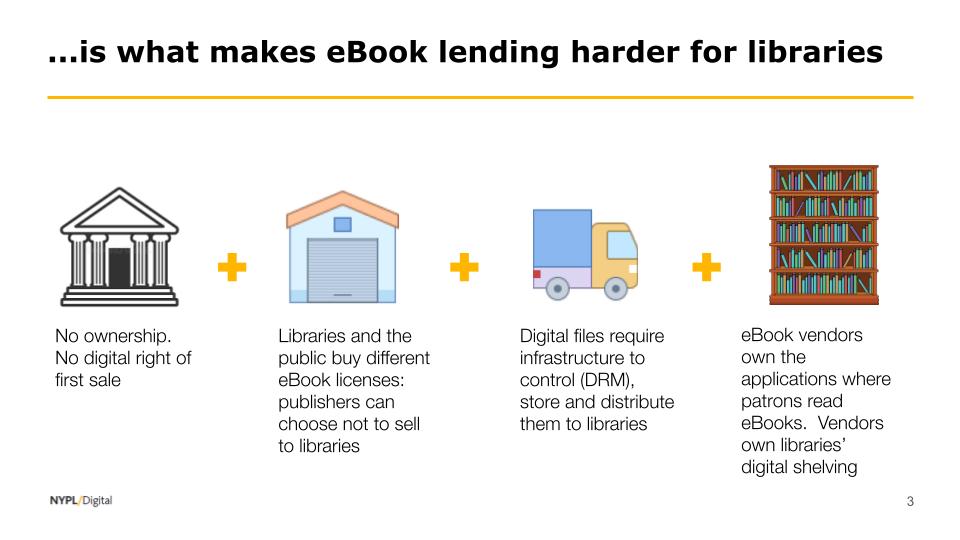

- None of these conditions are in evidence when it comes to eBooks.

- There is no confirmed first sale doctrine for software. Most publishers do not sell eBooks to libraries, they license them the same way Microsoft licenses Word and Excel. These licenses prescribe the terms under which we can lend eBooks. This will make sense if anyone has ever tried to give away their copy of Word.

- Second, because libraries are seeking to buy a bundle of licenses publishers are able to segment libraries and set different pricing.

- Third, while the digital file is wonderful in some ways, it has its own challenges to manage and control. That creates costs, requires digital rights management technology, and introduces middlemen into the process.

- These middle men, like Overdrive in the US, for most libraries provide not only the file hosting but also display of eBooks through their proprietary eReading apps like Libby. That means libraries no longer have neutral shelving. They cannot licence an eBook from one vendor and have it seamlessly show up next to our other eBooks.

- I want to suggest that eBooks fundamentally changed the nature of the publisher/library relationship from one that was fairly hands off, to one that requires more active engagement.

- There is very little variation in print books. There is almost nothing for libraries and publishers to enter negotiations over.

- As a result libraries and publishers have very specific types of conversations led by library book selectors/buyers and publishing house marketers.

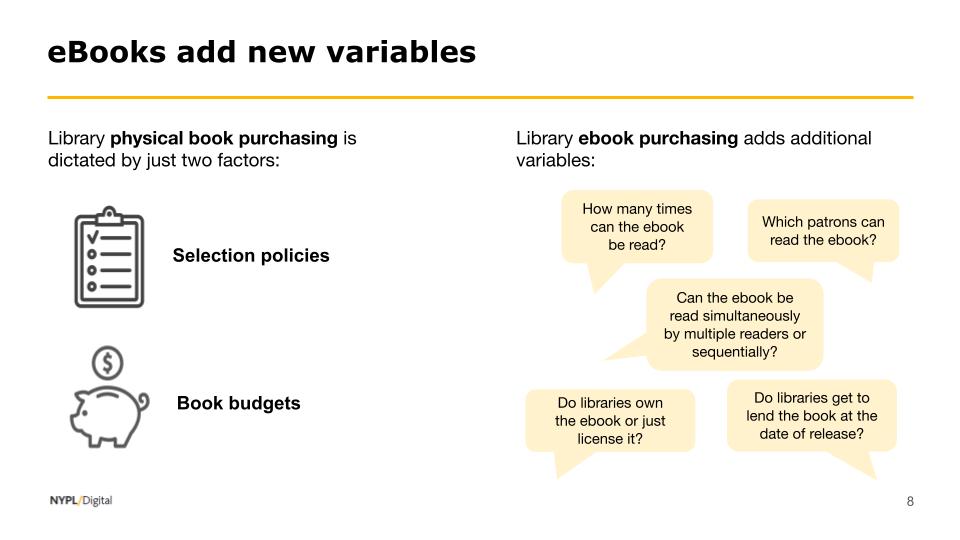

- When you are writing the permissions on a digital file there are an enormous number of variables that you can adjust. Some are listed above.

- Here is my understanding of how the terms for American public library eBook licensing evolved over time. About ten years ago, the major publishers started out licensing eBooks to libraries on a one copy, one user basis for a perpetual license at 5-10 times the list price. For example, a library could buy one electronic copy of the Secret Garden and have it forever to be used by one reader at a time. This looked like a good idea at the time and seemed to replicate the physical book market.

- However, publishers realized that for some titles they were losing the recurring revenue that came from a library purchasing new copies as old print copies wore out.

- Some publishers offered libraries the option to pay per use but this creates budget management challenges for libraries, like putting down a credit card without knowing how many people are going to be coming through the turnstiles.

- And where libraries and publishers have largely settled is one copy, one user model where libraries buy a package of lends. 26 lends or one year of use, whichever expires first.

- From this anecdote you can see that libraries are in a de facto negotiation with publishers however these discussions are almost entirely mediated by vendors or had through trial and error over years.

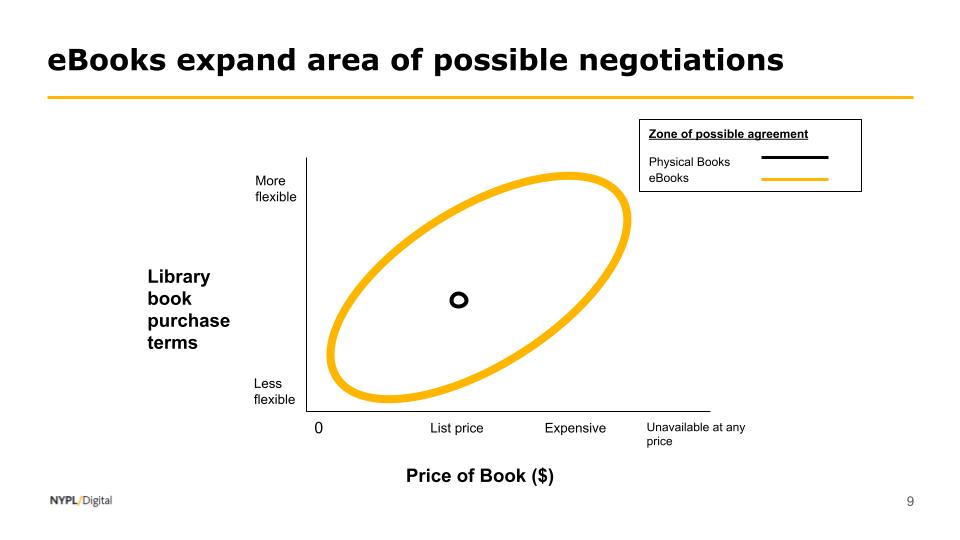

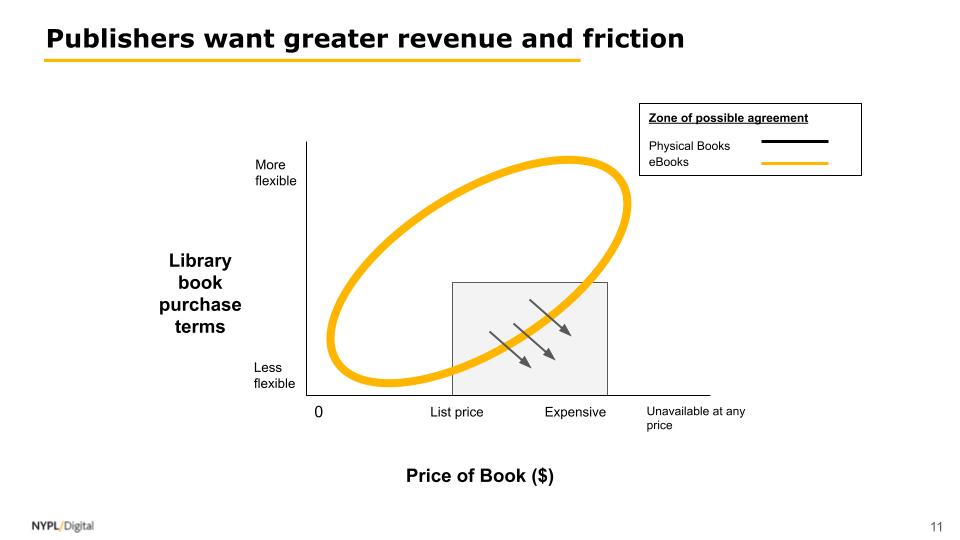

- This is an effort to visualize the change in parameters of negotiation for publishers and libraries.

- On the x axis is the price of the book. To the left it’s cheaper, to the right it’s more expensive.

- On the y axis are the terms. For the purposes of this image I’ve stuck to two dimensions so all the different variables we could negotiate on, other than price, are just lumped together. To the bottom is less flexible, to the top is more flexible.

- The black circle in the middle is the “zone of possible agreement” for print books. Public libraries can buy (or not buy) a print copy at roughly the same price as the average consumer. Even if libraries were inclined to sit down with publishers regularly there is not much to to negotiate. Publishers have a difficult time forcing libraries to pay over list price and libraries can’t offer publishers much to get them to lower their list price.

- By contrast, the yellow oval is the zone of possible agreement for eBooks. If libraries want multiple users at the same time, the price goes up. If they want it perpetually the price goes up. If the book is unpopular, the price could go down. If libraries can demonstrate our readers are not book buyers, the price could go down.

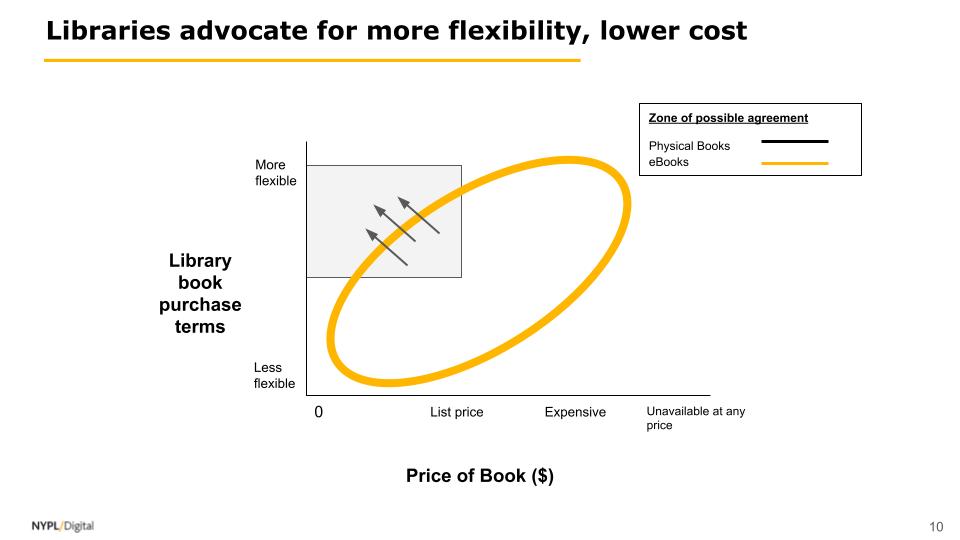

- For the past ten years public libraries have been advocating for cheaper pricing and more flexible terms. They want to push towards the top left quadrant.

- Over the same time period publishers have been pushing for more expensive, less flexible terms.

- You can imagine how this has been going.

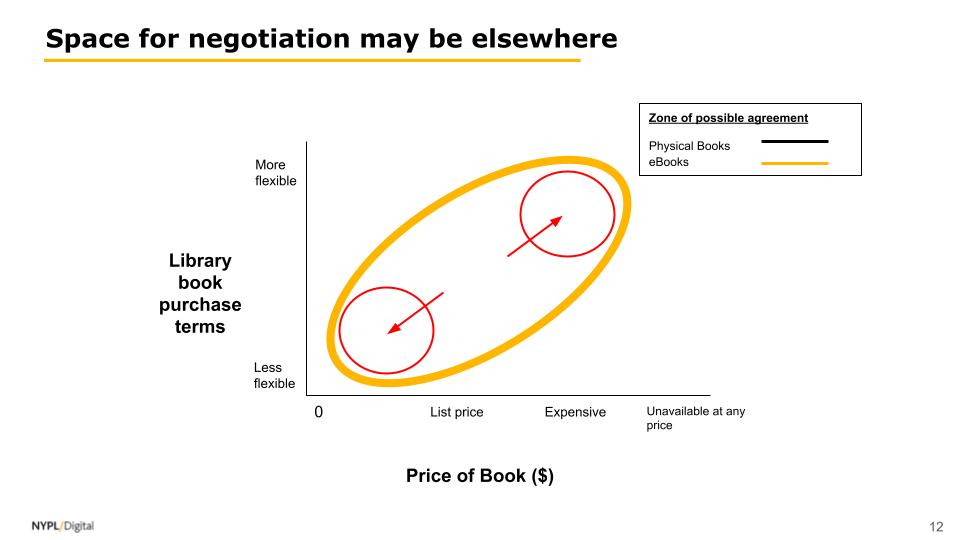

- In theory, there may be opportunity for libraries and publishers to explore areas for shared value.

- While this is mostly theoretical in the American market I can find evidence for it in Denmark with the work Mikkel has led. (More on this later).

- There is one other significant factor that needs to be addressed in the eBook supply chain and that is the role of the vendors who host our eBook licenses and also provide eBook apps used by every other public library in America. These middlemen have an enormous amount of power.

- Our print book vendors sell us books. Sometimes they do a little more to help us organize our data, but that’s about it.

- But because libraries aren’t technology companies, when our vendors started licensing eBooks to us they also needed to provide an app to read in.

- This app is the de facto digital library. It assumes almost all of the responsibilities of a normal branch library from organizing the titles, picking the target user, creating the user experience.

- Because libraries have very loose connections with patrons we have a difficult time telling patrons to switch apps. While a high school can tell students at the start of every year which apps to use, libraries tend to worry about losing readers when switching patrons from app to app.

- We’ve seen Overdrive make a series of strategic choices that change the willingness of publishers to do business with libraries. I mentioned one earlier. When they partnered with Amazon in order to help libraries serve their patrons, we lost Penguin book access. This dynamic has, to my eyes, no historical precedent for libraries.

Even if we can’t see it right now, what would success look like? This slide lays out a stab at an answer.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

It is very easy to see how digital technology has changed the reading experience of our patrons. It’s harder to observe how it has changed our business operations. We are at the beginning of thinking this through. And we are somewhat alone among our public library peers in doing this type of analysis. Which is why we’re excited to share it with you for thoughts and feedback and criticism.